Facebook Live Feed on the Caravan in Mexico

On November 3, 2020, Hurricane Eta made landfall in Honduras, flooding the valley surrounding the northern city of San Pedro Sula. Two weeks later, it was followed by Hurricane Iota, a Category 5 storm. With the land already waterlogged, the additional flooding was especially devastating. An estimated half a million people were displaced, and roughly a 100,000 took refuge in hastily arranged shelters. As rainwater rose above rooftops, others sought high ground on highways or the peaks of levees, where many remain to this day, living in shacks made of sticks and plastic sheets.

More than 540,000 Hondurans have lost their jobs since the onset of the pandemic. In November, many of these same people saw their homes and possessions disappear in the hurricanes. With rates of violence and unemployment persistently high in recent years, the only people in the country who have apparently managed to improve their standing are politicians and their cronies, who siphon funds from the social welfare programs meant to address the root causes of migration. In light of this, to many, emigration is the only option.

Even before the floodwaters had receded, Facebook posts started popping up advertising a caravan for the survivors of Eta and Iota, set to depart on December 10 for the U.S. border. Links to join WhatsApp groups soon appeared. All this followed the blueprint of most of the migrant caravans that have departed from Honduras since the very first, which left San Pedro Sula in 2018. That caravan was organized by migrants and accompanied by human rights activists, who ensured that it wasn't steered in the wrong direction. Although fewer than 1,000 people convened at the bus terminal on October 13, the day of the departure, press coverage helped the caravan explode in size. By the time it entered Mexico, more than 10,000 people had joined. When the caravan reached the U.S. border in mid-November, many began the long process of applying for asylum. Years later, that caravan remains the only one whose members made it from Honduras to the U.S. as a group.

Since then, more than a dozen caravans have left Honduras, though under very different circumstances. The criminalization of migration activists by the U.S. and regional governments at the direction of the Trump administration opened the door to shadowy figures who traffic in disinformation and exploit social media to take advantage of migrants. These are the characters who now organize caravans. Typically, they begin by circulating digital fliers for a trip on Facebook and WhatsApp. Then, as word spreads, local news outlets start covering the story. Often, journalists repeat the selling points used by organizers, unwittingly helping them to recruit more travelers. But concrete details — who is behind the planning, what the route will be — are usually left out. Over a period of nearly six months, Rest of World followed two different caravans as they were being organized over social media, then joined them on the ground as they attempted to head north.

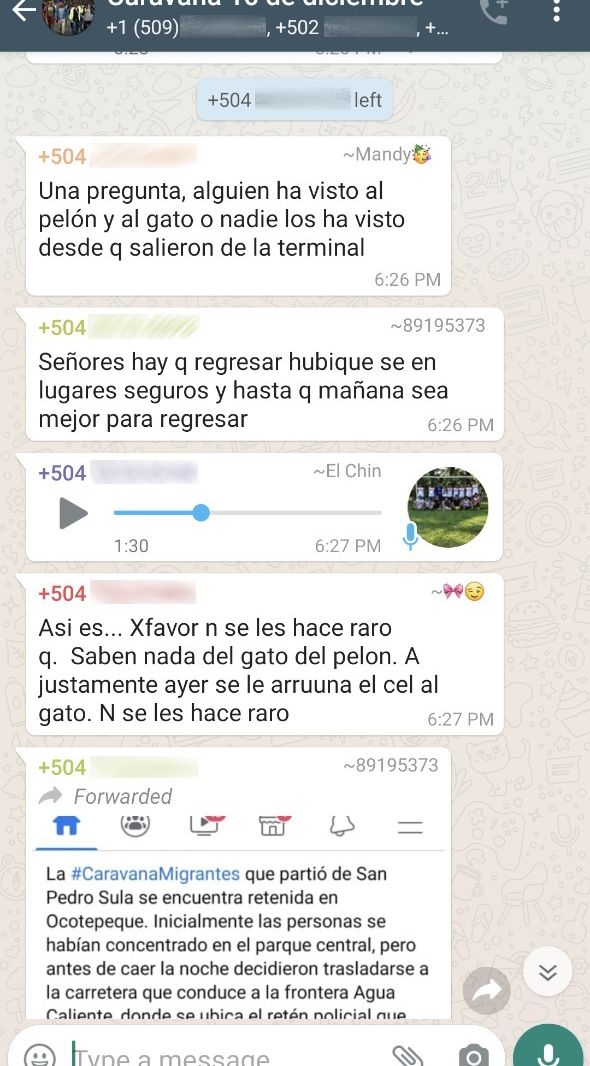

In the weeks leading up to the departure of the December 2020 caravan, organizers were in frequent touch with would-be migrants over Facebook and WhatsApp. (The companies did not respond to email queries about whether they were aware of what was taking place on their platforms.) Organizers checked in regularly to ensure that everybody was in high spirits, assuaged concerns about the dangers that lay ahead, and attacked anyone who expressed doubt about them or their prospects for success. The administrators, two individuals who went by "El Pelón," the bald one, and "El Gato Bolador," the flying cat, accused critics of being competitors or government agents. "Only positive people," they said when they expelled a so-called infiltrator.

This continued until three days before the caravan was set to leave, when ominous voice messages started to circulate in the WhatsApp groups accusing El Gato Bolador of being a trafficker who planned to sell the migrants to Mexican drug cartels. While some members heeded the warnings, others simply brushed them off. "Although it's Christmastime it's not like Santa Claus is going to lead us," wrote one.

Some suspected that the messages had been created by the leaders of a rival caravan scheduled to leave the following month. Antagonism between organizers is common on Facebook, with each side saying it runs the "real" caravan — not unlike a market where vendors all hawk the same product while accusing competitors of selling knockoffs. When El Gato Bolador reappeared, he deflected the accusations and quickly kicked out the person sharing the messages. There was no evidence to support the claim that he had ties with cartels. Nevertheless, there were other reasons for concern that would become apparent in the coming days.

On December 9, the day travelers from around the country were supposed to congregate at the bus terminal in San Pedro Sula, El Gato Bolador sent early-morning notes of encouragement over WhatsApp. "Don't forget God. God is going with us," he said. A little while later, however, he sent another message without explanation. "I'm going to leave the group," he wrote. "I thought you were the group," someone replied. It set off alarm bells, but by then it was too late: Many migrants were already on their way to the terminal, and the man who had promised to lead them to the U.S. border had vanished.

By that evening, around 500 people had gathered at the terminal, confused and rudderless. As panic set in, El Pelón sent a WhatsApp message telling people to meet him as far as possible from the bright lights of the TV crews that follow every caravan. But before anyone could find him, police moved in to enforce a pandemic curfew. The migrants had planned to spend the night in the terminal and depart at dawn the next morning, but instead they set out in darkness. El Pelón continued sending instructions, but always from a distance. In one voice message he passed his phone to El Gato Bolador to calm people's nerves. As this was happening, the group kept moving north. Eventually, they were stopped and forced to spend the night at a police checkpoint.

The next morning, migrants in the caravan started to arrive at the border of Honduras and Guatemala. Many tried to enter legally but were denied because they hadn't been tested for Covid-19; others slipped through blind spots along the border. El Pelón and El Gato Bolador later assured the group that they, the leaders, were already in Guatemala, but by then most people had become disillusioned and decided to return home. It had been less than 48 hours since they had said goodbye to their families, and the journey was already over.

No one ever asked the organizers to identify themselves. The possible presence of bad actors, combined with other factors — the ban on helping people traveling with caravans; the belief that state intelligence agencies infiltrate migrant WhatsApp groups — has made it an unwritten rule not to ask. Migrants, worried about kidnapping or extortion, advise their peers to avoid sharing personal information. This anonymity creates a climate of suspicion and lawlessness that is easily exploited. Xenophobes pop in and out of WhatsApp groups to insult and disparage Hondurans. Coyotes scout for new clients and advertise their services. Trolls harass female members and barrage chats with pornographic images and videos. A man in one group complained that, after changing his profile picture to an image of his wife, he began receiving direct messages from men trying to seduce her.

But the desire to escape desperate conditions often outweighs all else. Some migrants are fleeing from the gangs and organized criminal groups that have made Honduras one of the most violent countries in the world. Others are seeking better opportunities. The cost of living relative to the average wage in Honduras is among the highest in Latin America, and the traditional ladder out of poverty — hard work and a good education — has been broken. The more schooling somebody has received, the more likely that person is to be unemployed, according to the economic think tank FOSDEH. As a result, even before the pandemic and the hurricanes, the country was dependent on remittances. For those whose homes were destroyed or damaged by Eta and Iota, emigrating to the U.S. was the quickest way to recoup the losses.

At the same time, caravans are full of repeat travelers. The caravan that immediately followed the inaugural one fell apart after most migrants opted to apply for a humanitarian visa offered by the Mexican government. The rest have been compromised by pressure from local security forces or by their own disorganization. None of the more than one dozen that have departed in the past two years has made it to the border. Still, the next caravan won't be like the last, people tell themselves. This time, things will be different. No amount of suffering they might encounter on the road could be worse than what they face at home. So, despite the disappointing experience on December 10, many people behaved as if they'd missed a train and could simply catch the next one. They set their sights on a caravan scheduled to depart on January 15.

That 2018 caravan lives on not only in the minds of those who aspire to emigrate to the U.S., but also in the fears of American right-wingers. As that first group of migrants made its way toward the border, followed by scores of reporters, former U.S. president Donald Trump used it to stoke xenophobia. Tweet by tweet, he spread conspiracy theories about migrants and pressured his counterparts in Central America to crack down on caravans and anybody who might help them. The governments of Honduras, Guatemala, and Mexico — the three countries along the route from San Pedro Sula to the U.S. — bent to Trump's will.

Carlos Ramírez was one of several human rights defenders detained in the wake of these new policies. Having emigrated as a child to Mexico from Honduras, he was motivated by his own painful memories of that journey to help others in a similar position. In early 2019, while assisting migrants traveling through Mexico, Ramírez was forced into an unmarked van and placed on a flight to Honduras, where he was accused of human trafficking. He was eventually released because of a lack of evidence, but about a year later, after being lured back to Honduras by a spurious invitation to give a talk, he was recaptured and charged. This time, he spent a little more than a year in jail.

"I can't go somewhere and tell people how things work because immediately there will be phones taking videos and pictures of me that could lead to an arrest warrant."

The reason behind Ramírez's arrest and other similar ones was simple: It signaled to anyone who might wish to support migrants that there would be consequences. Bartolo Fuentes, a Honduran politician, journalist and human rights defender who accompanied the 2018 caravan, was arrested when it passed through Guatemala. Irineo Mujica, of the migrant rights group Pueblo Sin Fronteras, which also accompanied the caravan, was arrested in Mexico the following year, prompting widespread public outrage. As human rights defenders stepped back out of fear of persecution, shadow figures moved in to fill the void.

"It's evident that the caravans are no longer just motivated by the needs and the despair of the people, but also by individuals with hidden interests," said Fuentes, who says he remains under threat of prosecution. After roughly two decades of humanitarian work, he still keeps an eye on the caravans, but now from a safe distance. "I can't go somewhere and tell people how things work because immediately there will be phones taking videos and pictures of me that could lead to an arrest warrant," he said. He added that while governments have targeted activists with proven track records of helping those seeking to emigrate, he has noticed that authorities are willing to "protect — or at least tolerate — those who lead migrants in failed attempts to flee the country."

Theories abound about what motivates these new organizers. "When a person encourages another person to leave the country, I'm not sure what their end goal might be," said Ramírez. One of the more popular ideas is that they actually work for coyotes, accepting commissions when people decide to leave the caravans and travel with them. There is evidence to support this: It's common for migrants to end up hiring a coyote after a journey has begun, particularly during a caravan's final leg across the U.S. border.

Fuentes also floated the idea that the government may be paying organizers as a way to prod the U.S. for financial assistance. "For the [Honduran] government, the caravans are very beneficial because they take on great relevance for the United States," he said. Although only a small fraction of Honduran migrants arrive via caravan, they reliably dominate headlines. Whatever the motivation, the absence of activists such as Ramírez and Fuentes from these journeys is one reason why caravans are being led astray.

With the crooning voice of a much older man, 30-something caravan organizer Lester Gonzales invokes God more often than a bible salesman. "God will clear the path" is a favorite refrain of his on social media when attempting to calm fears about the obstacles ahead. Experience, however, would suggest it is warranted. One of his first known caravans, in October 2020, ended with migrants being intercepted by Guatemalan authorities. Another one, months prior, had been attacked with tear gas before reaching the Mexican border, where those still with it were eventually detained. Since the poster promoting that caravan conveniently mentioned only the day and month — January 15 — Gonzales recycled it for his most recent effort, on January 15, 2021.

While little is known about Gonzales except that he reportedly traveled with the very first caravan before starting to organize them himself, he has also not made any attempts to conceal his identity. His fingerprints were all over Facebook and WhatsApp groups for upcoming caravans, and although he did not respond to requests for an interview, he has been mentioned in press reports as the organizer of the January initiative. "This time it will be a very serious caravan, not like the last," he wrote in an October 2020 Facebook post, blaming earlier failures on unruly travelers. But many people who had trusted him in the past weren't buying it. Warnings about Gonzales popped up everywhere. "To those who are going on the 15th, know that you're going to fail. Lester is leading that caravan, he already failed four times," read one post on Facebook. Others accused him of having hand-delivered them to authorities in Mexico and of having led them into clouds of tear gas. In WhatsApp groups Gonzales followed the usual playbook: He deflected all accusations, labeled critics as "infiltrators," and exercised total control over who could access the chats.

Nevertheless, toward the end of 2020, his January caravan picked up steam. Facebook groups swelled in numbers and WhatsApp groups associated with his caravan multiplied until there were well over a dozen. Many people who lost everything in the November hurricanes had decided to skip the December caravan and wait for the January one so they could spend a final Christmas with their families. The coming inauguration of Joe Biden also contributed to the belief that it was the right time to emigrate. Online, organizers shared false and misleading information about the president-elect's proposed immigration policies, including that the asylum process would be immediately restored upon Biden taking power. As January 15 grew closer, local media unwittingly lent a hand to organizers by repeating their grandiose claims that the "mega caravan" would include as many as 20,000 migrants, which would have made it the largest ever.

On the evening of January 13, as thousands of people across Honduras prepared to set off for the bus terminal in San Pedro Sula, doubts about the organizers once again rose to the surface. "And this is your leader?" read one message sent directly to WhatsApp group members. "This jerk has organized caravans since 2019, why is he still in Honduras? This man is pure lies, he just organizes and I think intentionally separates people, who knows what kind of business he has. Careful with that Lester." Accompanying the message was a picture of Gonzales at the bus terminal with the caravan he had organized exactly a year prior.

A voice message that had circulated in the groups several weeks before also reemerged. The speaker accused Gonzales of belonging to a cartel, and noted, darkly, "When they're taking out your liver, you were warned." The voice was the same one that had spoken up in the December groups. "If I had doubts before, now they're much greater," a woman who was planning to travel with her son wrote in one of the WhatsApp groups. She had been aware of the rumors about Gonzales, but she admitted that she had chosen to ignore them until now. "I'm worried that the people who lead the caravan will just take us to Guatemala or Mexico and then we'll be sent back … If it's just going to be a trip, I'd rather spend my money and go to Tela," she added, referring to a popular beach destination on the northern coast of Honduras. Although many shared her fears and doubts, they had little left to lose.

The next evening, several thousand migrants assembled at the San Pedro Sula bus terminal. Seated on a grassy hillside by a parking lot, Julio Martinez and his family were confident that the caravan they'd traveled across the country to join would make it to the promised land. "They're not going to stop us, because God is going with us," said the 48-year-old father of two. "God will light the path." His wife, Karen Romero, had learned about the caravan a month before through Facebook. Because of the pandemic, the couple had both lost their jobs on the tourist-dependent island of Roatán, about 65 kilometers off the north coast of Honduras, and were on the verge of becoming homeless. With Biden's inauguration just five days away, they thought the time was right to risk it all. "The president has promised to fix the papers for 11 million immigrants," said Martinez, erroneously claiming that a proposed amnesty for undocumented people in the United States would apply to his family. "We had to sell all the little things we had in order to pull together enough money to come here and have a bit of cash for the kids," said Martinez, as his 7-year-old son and 8-year-old daughter pleaded for ice cream from a nearby vendor. Martinez wasn't sure who had organized the caravan, nor was he concerned. "No one is a leader here," he said. "We're all going together like the Honduran family that we are."

Soon after dark, Gonzales emerged from the shadows, a pair of children by his side, and announced that the caravan would leave as planned at 5 a.m. the next morning. To relay the message to everyone spread across the terminal and surrounding hillsides, the organizers played recorded messages through a megaphone. Voices that were by now familiar to many in the WhatsApp groups echoed across the landscape. Nervous and full of energy, few people got much sleep that night. The next morning, at 4 a.m., organizers walked the grounds to wake travelers up. When everyone was ready, they announced that the nonprofit Doctors Without Borders would be providing Covid-19 tests at the border for anyone who hadn't already gotten one and proceeded to count how many were needed. To legally enter Guatemala, each migrant required a negative test taken within 72 hours of the date of entry.

The group set off, and spent the day walking and hitching rides across the dry, rugged terrain. That night, as the sun dipped behind the mountains, around 5,000 migrants arrived at the Honduras-Guatemala border to find a wall of security forces dressed in riot gear. Gonzales, whose unusual height makes him easy to spot, was conspicuously absent. He had not been messaging with the groups that day, and the Covid-19 tests organizers had promised were nowhere to be found; they had simply been made up. Tired but determined to keep going, a small group of travelers formed a human battering ram and tried to push through the police line to cross the border. Significantly outnumbered, the Guatemalan authorities eventually let them through. The next morning, several thousand more migrants followed. It was a victory, but not a permanent one. Just ahead of them, Guatemalan security forces massed at a bottleneck on the highway, determined to stop the caravan in its tracks.

An estimated 7,000 to 8,000 migrants — large enough to make it the second-biggest caravan ever — were trapped. Violent confrontations ensued. Watching on TV or the internet, Hondurans agonized over scenes of their loved ones being beaten with batons. Family members unable to contact relatives shared photos on social media with desperate pleas for information. "There are people who can't sleep amid so much anguish," said a woman whose husband was part of the group. After nearly two days, exhausted, hungry, and faced with an interminable standoff, the migrants started to turn back. The caravan fell apart.

Meanwhile, after being absent for more than 48 hours, Gonzales suddenly reappeared in the WhatsApp groups to defend himself as questions began to surface. The last time he had been seen with the caravan was in the town of La Entrada, about an hour's drive from the Guatemalan border. "Unfortunately, they detained me," he said in a voice memo, "they said that I couldn't pass because I had my two children." He shared photos of himself speaking with representatives of a human rights organization, his kids in strollers. The photos were taken at the border, but the landscape was suspiciously empty — no migrants were anywhere in sight.

Yet again, another caravan had failed within days of its departure. To many, this was a setback, not an ending. Until domestic circumstances improve, there will always be people willing to gamble on these trips, to take their chances until they eventually succeed. At the same time, travel itself has gotten increasingly difficult: Human rights workers are gone, security forces wait for caravans at borders, and towns that once welcomed migrants with food and open arms have grown tired of the crowds.

Before most had even made it back home from the January caravan, a group of migrants began organizing a new one set for March 30. This one would be different, they said. The myth of the first caravan, and the pursuit of the American Dream, lives on. Back in San Pedro Sula, Julio Martinez said he was also determined to try again in a few months. He worried about how he would be able to feed his family if he stayed in Honduras. As a woman in one of the groups put it, "I'd like to say don't go and suffer more with the caravans … but the problems in our countries make that impossible."

Ultimately, only a couple hundred migrants joined the March caravan. This was despite the best efforts of a new organizer, who created his own Facebook and WhatsApp groups and even a website to promote the trip. Like countless others before it, that caravan was quickly dispersed by security forces. Soon after, the organizer began recommending that migrants travel in small groups to avoid detection and started posting to his Facebook group advertisements for "travel services to the United States" for $8,500 per person. Meanwhile, others, undeterred by the past, also launched their own campaigns. On Facebook, they started calling for a new caravan to depart on May 30.

Source: https://restofworld.org/2021/how-migrant-caravans-are-organized-and-scammed-via-facebook/

0 Response to "Facebook Live Feed on the Caravan in Mexico"

Post a Comment